TACTICS OF ERASURE INTERVIEW:

ALBERTO LULE, MILLER ROBINSON,

RYAT YEZBICK, AND FAFNIR ADAMITES

Our summer Development and Education Intern, Emma Kramer, interviewed four of the artists featured in our juried exhibition Tactics of Erasure and Rewriting Histories. Read on to learn more about them, their art, and their interpretation of the central themes of the exhibition.

You can also click here to find a list of books, articles and videos recommended by all of the artists featured in this exhibition. The file includes clickable links for your convenience.

Read Alberto Lule's interview below, or click to jump Miller Robinson, Ryat Yezbick, or Fafnir Adamites.

Alberto Lule

He/Him

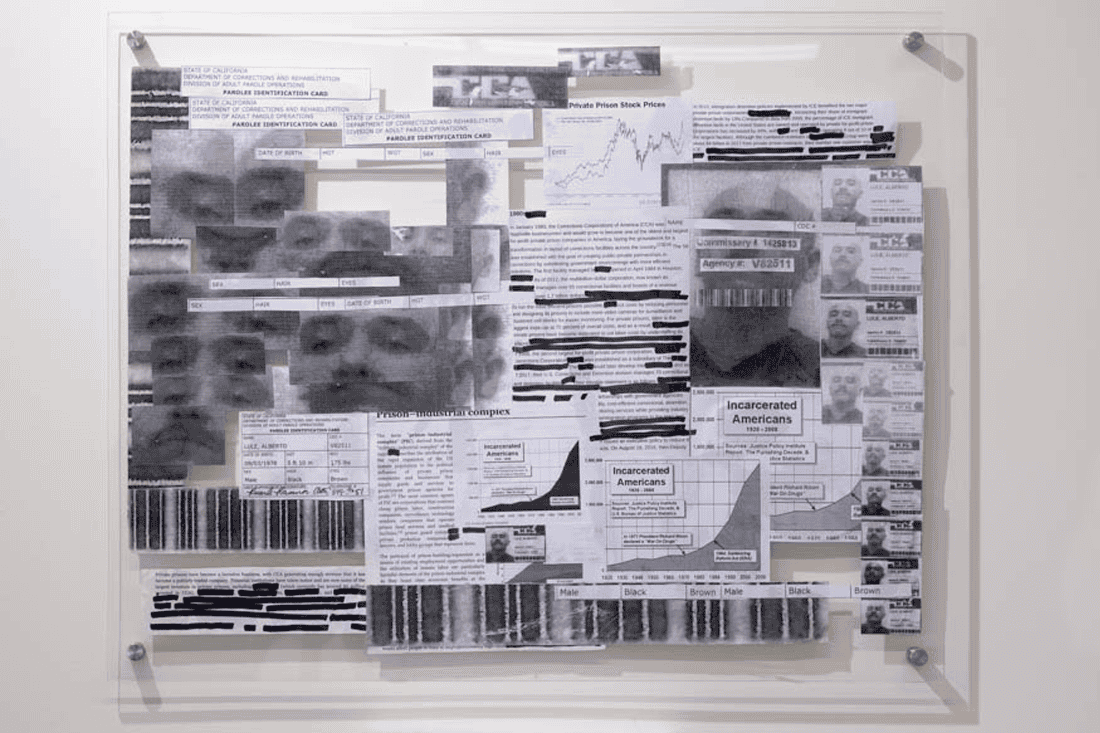

Image: Alberto Lule, Am I Truly Free (a), 2022. Collage on plexi. 18 x 24 inches.

Courtesy of the Artist. Photo credit: Andrew Girosetto.

To introduce you to those who may not be familiar with you or your work, who are you, and how would you describe yourself as an artist?

Alberto Lule is an American Artist who identifies as being Formerly Incarcerated. Lule uses readymades, mixed media installations, video, performance, and tools used by agencies of authority to examine and critique the prison industrial complex in the United States, particularly the California carceral state. Using his own experiences, Lule creates artworks that explore institutional roles as gatekeepers of knowledge, authorities of culture, administrators of discipline, and punishment.

What does the idea of erasure mean to you?

The idea of erasure is a very violent act. Whether it be the erasure of identity, culture, or history, on a broad scope, is a very violent gesture. Even on a smaller scale, with a pencil and eraser, the idea of rubbing out what once was, because one did not approve of what was written, is a violent motion. This concept has been desensitized through technology. The idea of deletion now with a keystroke rather than a pencil and eraser, only shows us how desensitized, insensitive, and banal this very violent gesture has become.

Is there a material you prefer to employ in deconstructing dominant narratives of history?

There are several materials I use when thinking of deconstruction. One in particular is the forensic latent fingerprint powder. It is not a traditional material used to make art. It is a tool used by agents of authorities to discover evidence in a crime, left behind by a perpetrator. It makes me think of the Audrey Lorde book and quote: “The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House.” My theory on using this material is: If you believe, as I believe, that the criminal justice system in America is biased, then the tools, training, strategies, and techniques used to apprehend, detain, arrest, and indict criminals within this system must also be biased. It is here where I overt, subvert, invert, and pervert the material, aiming to investigate the investigators, to begin deconstruction.

How do you feel that your art challenges existing systems of oppression?

I believe American art is still heavily influenced by Modernism. Like the Postmodernist of the turn of the century, I aim for oversion, subversion, inversion, and perversion of these modernistic modes of art making, with the aim to deconstruct the power structures that dominate American contemporary art. I believe what I can do is begin to create the art from the perspective of living the actual experience of being investigated. The actual experience of being imprisoned. I believe we are living in times where the oppressed peoples of the world have the ability to control the narrative. For example, I am in a position now to give you the narrative from the perpetrators perspective, not just the investigator. Not just the researcher or the academic. When the prisoner, the gang member, the immigrant, the human trafficking survivor, the oppressed, control the narrative, that is abolition. That is revolution.

Jump Back to Top | to Miller Robinson | to Ryat Yezbick | to Fafnir Adamites

Miller Robinson

They/Them/It/Its

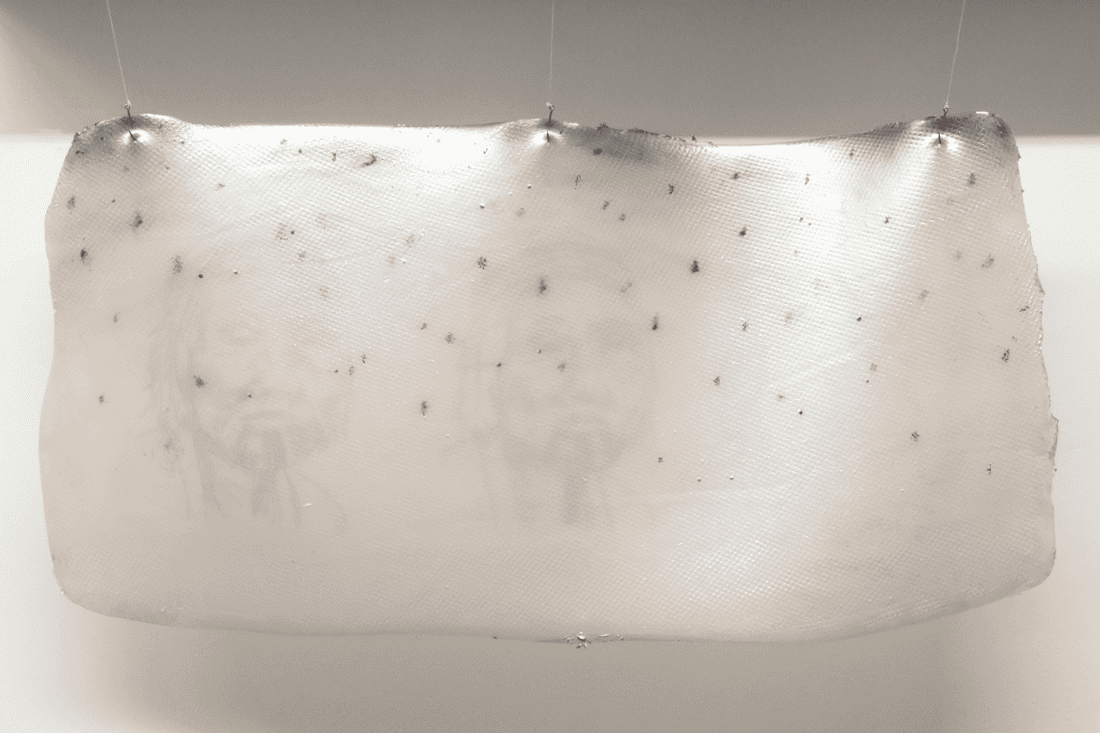

Image: Miller Robinson, Áama (salmon) Skin, March 2021. Graphite-transfer and pearl-ex pigments on silicone rubber, monofilament and fish hooks. Courtesy of the Artist.

To introduce you to those who may not be familiar with you or your work, who are you, and how would you describe yourself as an artist?

Ayukîí, my name is Miller Robinson and I am a trans, two-spirit artist of mixed Karuk, Yurok, and European descent. As an artist, I am tethered by sensitibilites that prioritize collaboration, storytelling and the passage of non-linear timelines. Themes of transfiguration, temporality, and care are routine to my process. I work in constant dialogue with the state of materials, often informed by other-than-human kin, basket weaving and fix-the-world People. Through performance and sculpture, I incorporate garment-making, poetry, tattooing, and installation to create detailed ecosystems in exhibitions that seek our horizons in Queer and Trans potentialities.

What does the idea of erasure mean to you?

The idea of erasure feels like a dichotomy, a paradox, or like a multiplicity that presents itself as a singular gesture. Erasure is an act of dominance informed by the person(s) or culture enacting it, it is about proximity and relativity. I think it's about loss and acknowledging a specific position to loss— it's about grief for me.

There is a deep longing attached to this idea of erasure and I explore that in my work a lot. To be vulnerable to erasure touches on temporality, a transition I try to direct toward seeing new beginnings.

A cycle of erasure always leaves residue, no matter how subtle or unperceivable or altered, contingent on scale. Erasure feels like an attempt more than an obliteration.

The idea of erasure is hard to quantify or locate which is why it's a concept I explore in so many various ways in my work. Erasure can be as much about covering up as it can be about removal. I cling to knowing DNA and the land hold what has and will always be, even if certain data, information, memories, or histories have been buried, hidden, or are sleeping.

Erasure is one of those nouns that is intricately attached to a verb or action, the idea of it lies within how and when and where not just what is involved. As someone who’s identity confronts attempted erasure from different intersections, the idea of erasure always leads me to the idea of adaptation that is needed to survive when something is threatened or endangered, the two feel inseparable for me.

Recently, I have been using processes of erasure in my work as reclamation, to create privacy and illegibility as a means for protection and self-preservation. By using processes that disguise or obscure or camouflage, I can slow down the disclosure of sensitive information or for cultural confidentiality. I want erasure to become an act of refusal in that regard.

Is there a material you prefer to employ in deconstructing dominant narratives of history?

I don’t have a preferred material but I think a lot about the properties of materials when approaching how to deconstruct dominant narratives in history. When thinking through specific narratives or research, materials are critical to the experiences associated with them. I believe materials are living collaborators and the ways in which I deconstruct dominant narratives is through the processes by which I transmute, transform, or reframe specific materials in ways that collapse, combine, disguise, camouflage, reveal, or conceal aspects of the materials themselves as well as the content of the works like the imagery, information, compositions or forms being explored. World-building is the method at which I arrive at deconstruction. Materials I have used in the past include things like dust, my own hair, my blood or the blood of collaborators, salt, egg yolks, soap, plaster, wood, ash, latex, silicone, specific metals and so many more.

How do you feel that your art challenges existing systems of oppression?

This is something I think about a lot and also question a lot. I think that the process of questioning is really important to challenging systems of oppression and I hope my art prompts questions in people. Right now, the way I feel my work challenges systems of oppression lies somewhere within how I explore time and existence in a non-linear way. It's kind of about slowing down and taking time to try to learn really intentionally, about paying attention to all the details and overlaps, and honoring the nuanced experiences of the people and other-than-human kin I work with.

Within systems that use extraction, exploitation, manipulation and constant distraction to control us, my work aims to unravel harmful myths while offering other ways of thinking or seeing or doing. I guess it's about living between worlds and inviting people into that space with me. I’m constantly working through how my art functions as I medically transition, navigate neurodiversity, and reconnect with culture.

An emphasis on healing feels powerful when challenging existing systems of oppression for me. My work feels like an impulse or an entry point for self discovery and undoing trauma, within its joys and hardships. Recently, the work has been touching on a lot of the painful parts of being a person and trying to find recovery or something generative in that.

I’m really just trying to process this thing I call existence and myself, and my art has been a literal tool for surviving personal and intergenerational trauma. I don’t know if that challenges existing systems of oppression or not, but it feels huge to me.

My work is super personal, it's a really vulnerable process that’s hard to talk about sometimes but I hope it can uplift or reach people that are in pain or maybe don’t understand aspects of themselves the way I didn’t and often still don’t.

I hope my work can destigmatize or expand on experiences of gender, sexuality, mental health and connecting with culture or self or land. The work feels like an open invitation, not an arrival point. There's an emphasis on going and moving toward future selves that feel more in alignment or maybe just says fuck you to assimilation and conformity. It's not about a fixed position or a fixed end/product. My art is a verb. It is becoming.

I think a lot about the ways in which I go about making art as challenging oppressive systems for myself that could be a metaphor or mirror for others. For me the process is a way to my own liberation, the studio is a safe place to explore all the messy, scary, confusing stuff and find some kind of resolution in it.

My work seeks to be about grace and about learning and unlearning, about letting perceived flaws or scarcity become the exact moments of beauty and abundance that’s needed. The work is alive and never finished, it constantly ages or shifts, the materials I use require care —sometimes consistent care. I don’t want that to go unnoticed or unacknowledged, I want to celebrate that more in the work actually because it teaches me how to care for myself and for others.

Sometimes the work requires surrendering to precarious timing or to the incompatibility of forms that are not meant for preservation. It’s a practice in letting go or understanding limitations, in forming connections and having respectful relationships.

My work attempts to refuse assimilation and conformity through the way I presented it in different ways within its varied non-linear existence, or at least that's the trajectory. Both my art and myself are adaptive shapeshifters that seek to undo, redo, expand—letting things become transformed, reabsorbed, or released over time.

I live with my art, I talk to it, sometimes we don’t get along and I have to learn to understand it and live with it and love it over and over again. It’s kind of the familial structure I always needed but I never had access to. It is a really active intentional relationship which in itself feels like it challenges how art and connections function within systems of commodification, ownership, and exploitation.

Jump Back to Top | to Alberto Lule | to Ryat Yezbick | to Fafnir Adamites

Ryat Yezbick

They/Them

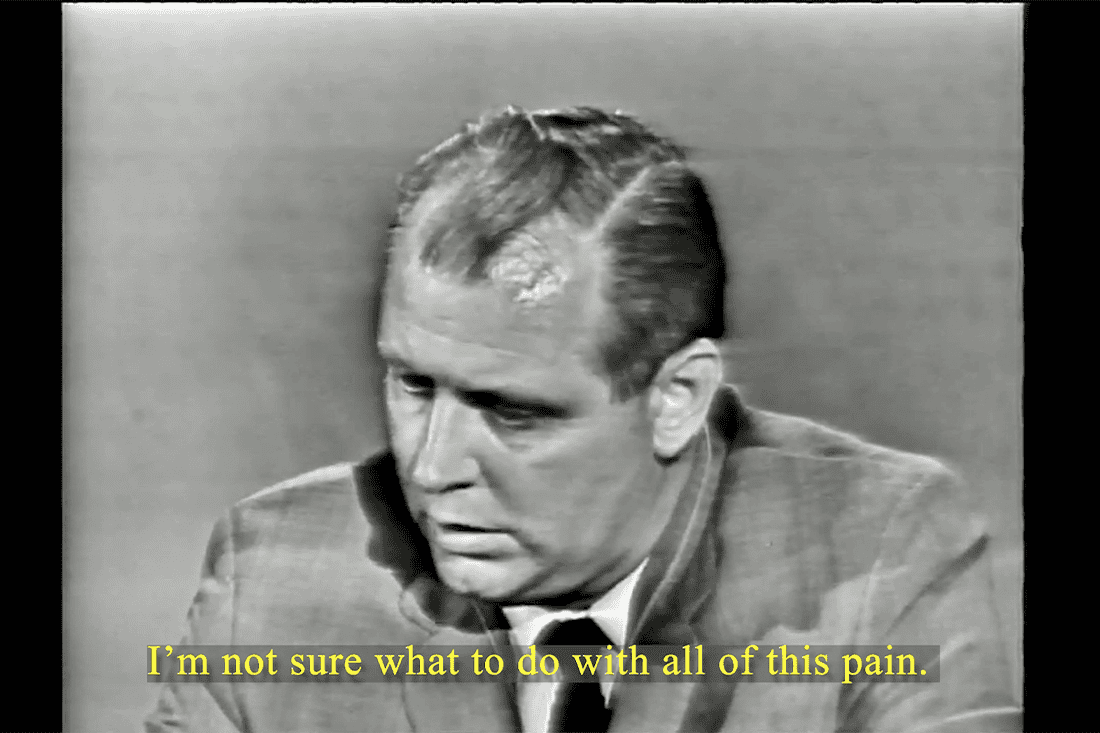

Image: Ryat Yezbick, growth lies, pack of truth, 2022. Video still. Courtesy of the Artist.

To introduce you to those who may not be familiar with you or your work, who are you, and how would you describe yourself as an artist?

My formal training as a cultural anthropologist impacts the strategies I employ as an artist. I like to look structurally at social histories of oppression by carefully examining patterns over time in order to understand how recurring beliefs and attitudes morph and impact our collective outlook in the present. I am particularly drawn to investigating the U.S. cultural relationships of witnessing, group identity, and contemporary morals in the era of digital surveillance and decentralized global conflict. Through my inquiries, I place my lived experience centrally in my work, addressing a complex set of questions around security, home, family, love, violence, power, and responsibility.

I have a pretty consistent through-line in my work from anthropology to art. As an anthropologist, I worked with Arab and Muslim American spokespersons in Detroit, Michigan to understand how the events of 9/11 impacted notions of citizenship amongst the neighborhood’s residents. For example, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) opened its first office in the heart of this community the day after 9/11. The ongoing government surveillance, coercion and state-sponsored terrorism of this community cannot be understated. I am third generation Lebanese-American, and it is painful to hear of all the ways this community has been deliberately isolated, targeted and watched by our government.

To this day, my work engages critical questions about how surveillance culture creates and reinforces the production of racialized others as potential threats to the State or as bodies to be monitored, incarcerated, deported, or coerced into assisting the national project. My latest body of work looks at these issues from a different angle focusing on the self-identified white American, assessing how news media and surveillance culture have conversely engendered a passive white subject. growth lies, pack of truth, which is currently on view at Craft Contemporary, creates a fictional narrative out of news media coverage of mass shootings since the 1960s. The film features an interview conducted by a news anchor with a first responder during the 1966 University of Texas tower shooting and reimagines their conversation as a heartfelt discussion around the trauma of gun violence.

What does the idea of erasure mean to you?

I love this question. It really piqued my curiosity, so I looked up the definition out of interest. Oxford Language Dictionary gives two definitions for erasure:

- “the removal of writing, recorded materials, or data.”

- “the removal of all traces of something; obliteration.”

The second definition breaks my heart when I think about the extreme violence inflicted on so many communities that don’t fit the script of mainstream America. To not have a voice or say in society, in politics, in the communities you reside in, to be stripped of your voting rights, is its own kind of obliteration. This is a kind of forced erasure. If I imagine erasure as something one chooses, my emotional relationship to that word changes slightly. It is a kind of empowerment in which I could choose to redact or remove parts of myself from the public eye (my Facebook profile for example, aka my data) without any corporation being able to find and use my data for profit. I, however, see this as empowerment only as it relates to a disempowering system.

There is something inherently violent about the word to me, as something done to another or as an act done to oneself in order to evade dominant structures. In either valence of the word, there is an opposing force that is either provoking or evoking the erasure itself. I therefore feel the word directly references violence enacted within power structures. I can’t say this is evident in the definition of the word itself though.

Is there a material you prefer to employ in deconstructing dominant narratives of history?

Yes, most certainly. I love working with the moving image and specifically archival images, using history to contest history, you could say. There is nothing objective or neutral about the photographic image, and I enjoy eliciting other angles of the images themselves to construct new ways of seeing the past, present and future. Additionally, I am often drawn to using 3D imagery in artworks that indirectly reference the images’ military logic to deconstruct how such images have become embedded in the most mundane of life’s affairs.

How do you feel that your art challenges existing systems of oppression?

I draw attention to how historical patterns show up in the present, providing critical historical context so that the viewer can walk away from the work with a new understanding and felt emotional response to the topic at hand. I use both direct and discursive strategies to address salient political issues so that the viewer has space to insert themselves in the work. Sometimes I do so through explicit narrative and re-enacted conversation, other times I look for patterns repeating in archives in order to challenge dominant narratives. I also tend to tackle overt political issues that are frequently reduced to essentialist narratives in dominant discourse, intentionally creating more nuanced and emotionally complex terrain for the viewer to engage the issue.

Jump Back to Top | to Alberto Lule | to Miller Robinson | to Fafnir Adamites

Fafnir Adamites

They/Them

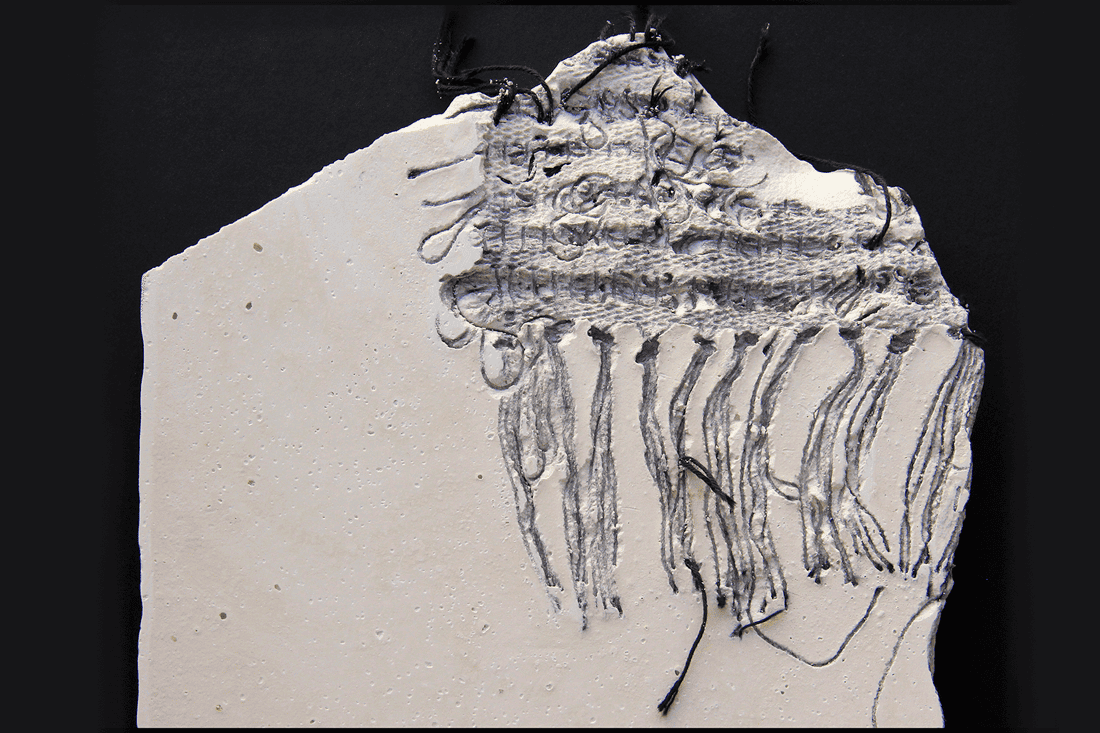

Image: Fafnir Adamites, The Presence of Absence, 2019. Hydrostone, cotton string.

Dimensions variable. Courtesy of the Artist.

To introduce you to those who may not be familiar with you or your work, who are you, and how would you describe yourself as an artist?

I am an artist and educator, recently relocated to the LA area from Western Massachusetts for a Tenure Track teaching position at California State University in Long Beach. I am teaching studio art classes in the Fibers and Foundations areas. An element of making that is important in my studio practice is embedding meaning into materials. It's a visual language that comes from deep knowledge of the materials and techniques being used. My work deals with inherited trauma and absence - two (of many) concepts that I find are extremely challenging to represent in physical form. This is why I look to the inherent qualities of the techniques (such as the repetitive nature of weaving) and the abilities of the materials (such as the ability of the Hydrostone to represent the memory of an object).

What does the idea of erasure mean to you?

The idea of erasure sparks in me the urge to find a trace, a hint, or an essence of the person/place/thing that is absent. It makes me want to find some kind of evidence as a way to preserve, to honor and to make known. Even if that evidence is a speck of sand or an impression of an object that no longer exists. An erasure is traumatic and it can have long lasting consequences. In my research I have looked to the Counter Monument Artists in Germany and their strategies of upending the authoritarian nature of public monuments when trying to remember those lost in the Holocaust. They do not seek closure. Instead, they build spaces where the memory can be engaged, where interaction is valued and no one is forgotten.

Is there a material you prefer to employ in deconstructing dominant narratives of history?

My focus on using traditional fiber materials and techniques is one way that I can push against dominant narratives. For example, the history of women's work is replete with examples of fiber techniques such as weaving and spinning that have been socially devalued yet have been critical to the development of civilizations around the world. Some of these techniques, like embroidery and quilting, have been used by marginalized people to have a voice and tell their stories in a world where they have no other opportunities. Utilizing these kinds of techniques in a fine art context (which has also devalued fiber as a mere craft form) is a powerful way to bring some of these histories to the surface and allow them to be seen in a different context.

How do you feel that your art challenges existing systems of oppression?

Taking up space as a marginalized person is one way to challenge existing systems of oppression. Materially and physically representing hard subjects such as trauma and bringing them into the public sphere is another way. Using ephemeral materials like paper and cloth rather than enduring, long lasting materials like metal is yet another way. As an artist, a person and an educator, I strive to work from a place of empathic softness which is inherently resistant, expansive and inclusive - a quiet yet powerful subversion.

Jump Back to Top | to Alberto Lule | to Miller Robinson | to Ryat Yezbick